The post below is (p)re-printed with kind permission from the Utrecht student media and culture journal BLIK, where it will appear in slightly altered form as the introduction to a special issue comprising the essays of first-year students in my class on the Humanities Honours Programme. The HHP is designed to offer additional depth, breadth and social engagement to students’ regular degree courses in the Humanities. Perhaps more importantly than that, to motivated students – and to us lucky teachers involved – it affords an opportunity to approach teaching and learning differently. As I have noted in earlier blogs (here, here and a bit here), the HHP has been a very important part of my thinking through what this whole teaching thing is about. It is probably where I have learned most about teaching, and about who I am as a teacher. It’s been an opportunity to embrace experiment and failure with students. It’s been a place to sit with students and think about the challenges we face and the tools we have to face them. The increasing threat of decimating budget cuts has meant that this programme was in line for the axe this year, and was only saved through the forthright intervention of faculty and students. I’m re-posting the essay here not so much as an introduction to the issue but as a kind of love-letter to the discipline, the programme, and the amazing students I get to teach as part of every ‘normal’ year.

Perhaps one of the most enduring issues to face students (and teachers, I will add!) of media and cultural studies is having to explain to people what it is we actually do.

As nearly every introduction to the discipline points out – whether it is recent or decades old – ours is a relatively young discipline, and one that is in turn marked by a high level of interdisciplinarity. While the objects of study (media) are in the very name, the form of those objects has changed rapidly since the founding years of the discipline, and their centrality to our work also remains a topic for debate (see Krajina, Moores, and Morley 2014). So what does it mean to be ‘doing’ media and cultural studies here and now? In both the 10- and 20-year anniversary issues of Television and New Media, a number of prominent names in the field were asked to take positions on this very question, both giving an extremely broad view of the field before us (Miller 2009; Ong and Negra 2020). As Ong and Negra note in their introduction to the 2020 issue, ‘our discipline’s agendas have always been diverse, and our prescriptions never standardized’(p. 556). As the teacher of the Media and Culture branch of ‘Explorations’, the opening course of the Humanities Honours Programme (HHP), I decided to make defining the discipline for ourselves the central challenge for students.

In the opening weeks of the course we read the seminal essay ‘Culture is Ordinary’ ([1958] 2014) by Raymond Williams, and every year it finds new resonance. Taking up the first term, ‘culture’, Williams insists that it must refer both to what we would call its anthropological definition as shared meaning and practices, as well as ‘the arts and learning – the special processes of discovery and creative effort’ (p. 3). Building on his own experience growing up working class in rural Wales, his claim that culture is ‘ordinary’ is that these two senses of culture, both community and tradition as well as creativity and progress, are normal parts of life for everyone. In exploring the implications of this claim, he models a further pillar of our discipline: its critical aspect that constantly considers the way in which both society and academia live up to the values they proclaim, and the hope that things can be improved. While Williams’s examples are bound up in the concerns of his historical position (as he would insist all analysis must be), and the tone and style are very different from academic work students are used to, as Jilly Boyce Kay highlights in her recent discussion of Williams’ legacy, we nevertheless see thoughts and struggles that feel ordinary – and urgent – in the discipline now. These include the fact that his analysis of culture is situated in, and validated by, his experience and social position. Expanding on that idea, Williams calls for academic enquiry and education that is fully embedded in the society it serves and is able to incorporate the meanings and lives of those that have been historically marginalized. Drawing on Marxism (another rich tradition of thought in the field), he insists that the material conditions of life matter, but asserts in contradistinction that culture cannot be reduced to them. His assertion in this essay that ‘there are in fact no masses, but only ways of seeing people as masses’ is an oft-repeated axiom of what became reception studies (p. 10). He closes with concern about the role of commercial media in relation to democracy, which feels like an urgent echo of the current questions surrounding the public value of privately-owned media platforms (Dijck, Poell, and Waal 2018).

As its final essay, ‘Explorations’ asks students from the domain of Media and Cultural Studies to step into the shoes of Williams and the authors in the special issues of TV&NM mentioned above and answer the question: ‘What, according to you, should be a ‘normal’ concern of media and cultural studies?’ The class itself forms one version of an answer: borrowing a synonym of Williams’s ‘ordinary’, its point of departure is the operating thesis is that the question of the ‘normal’ is the central concern of our relatively young and diffuse discipline. While certainly not unique to the discipline, critical questions of how, when and where certain times, places, things, bodies, behaviours, or experiences become ‘normal’ within our constantly shifting and highly mediated societies and environments are perhaps uniquely at the core of media and cultural studies. They are central in our understandings of (media) power and meaning, and sit at the heart of theories of ideology, discourse, representation, performance, and media domestication, to name just a few. To take another idea from Raymond Williams, the word itself can be seen as a ‘keyword’ in our society: both self-evident in meaning, but complex, varied and changing in connotations and contexts. In trying to grasp ‘normal’ in its multiple meanings (familiar, ordinary, predictable, standard(ized), privileged, etc.) and guises (sometimes as an experience, sometimes a value, sometimes measurement) we explore different strands of thought in media and cultural studies and see what insights into our present (and past) conditions we can gather. This exploration begins in with Titchkosky’s consideration of ‘normal’ as a keyword in disability studies (what was once a periphery and is now increasingly central to the discipline), and takes in objects of study ranging from SpongeBob (who shows up in Halberstam’s Queer Art of Failure) to machine learning and mops as highlighted in Shannon Mattern’s ‘Maintenance and Care’.

What is asked in the course, and in the essay, however, is not a summary of these various concepts and approaches, but rather that the students use them in a form of echolocation through which students gain a sense both of the discipline and their position in it. Our Utrecht colleague Annette Markham has theorized echolocation as the process by which we build selves in the digital world, with a constant set of pings and responses. Instead of assignments fixed on close readings or analysis, students are asked each week to give some form of ‘ping’ in response to the readings: keywords, photos, short writings, etc. Then in class, as noted below, these are transformed each week through discussion and collaboration into something collective: mind maps, poems, visual art, which students can use in turn as another ping of location. This work is then meant to build toward the reflections collected here in the special issue you are now reading, the last collective output of the class. Trying to take a position in the discipline at the start of the second year of a BA is no small feat, but like any academic communication, they are not meant to be a final statement, but one utterance in an ongoing conversation: they are pings that say where we are now. These pings are as widely varied as one would expect and hope from a diverse group of Dutch and international students, though each in its way shows an echo of Williams.

At the end of “Culture is Ordinary,” Williams grants himself three wishes for the future. First for an inclusive education system, second for increased public provision for ‘adult learning and the arts’ and finally for institutions of media and culture that are not driven by corporate profit, and specifically advertising revenue, and instead served public value independent of politics. In the final class meeting of ‘Explorations’, I turned these wishes into an assignment, in which each student was asked to make:

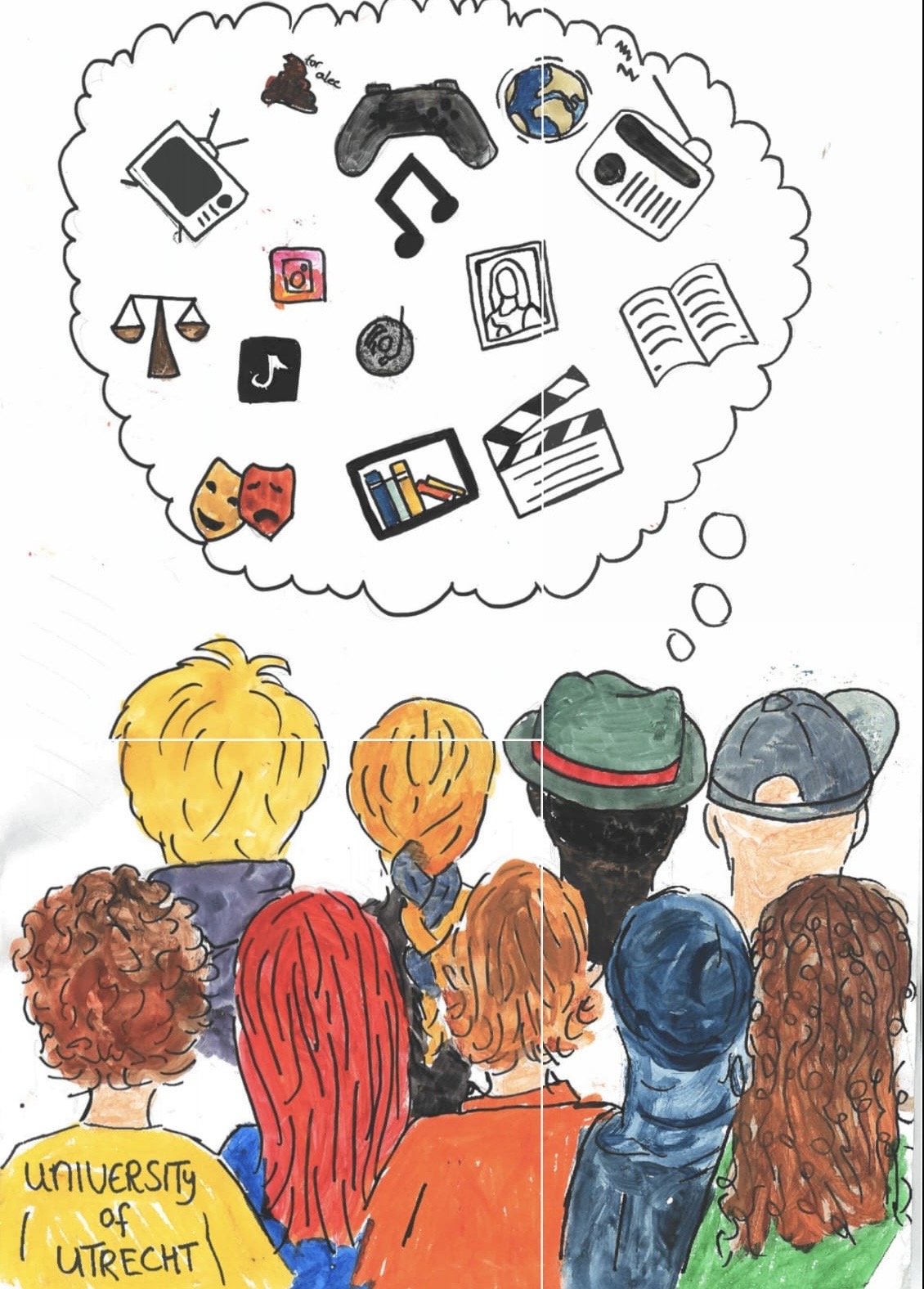

- One wish for the outcome of your study in Media and Culture

- One wish for the future nature of universities

- One wish for the form and content of future media products

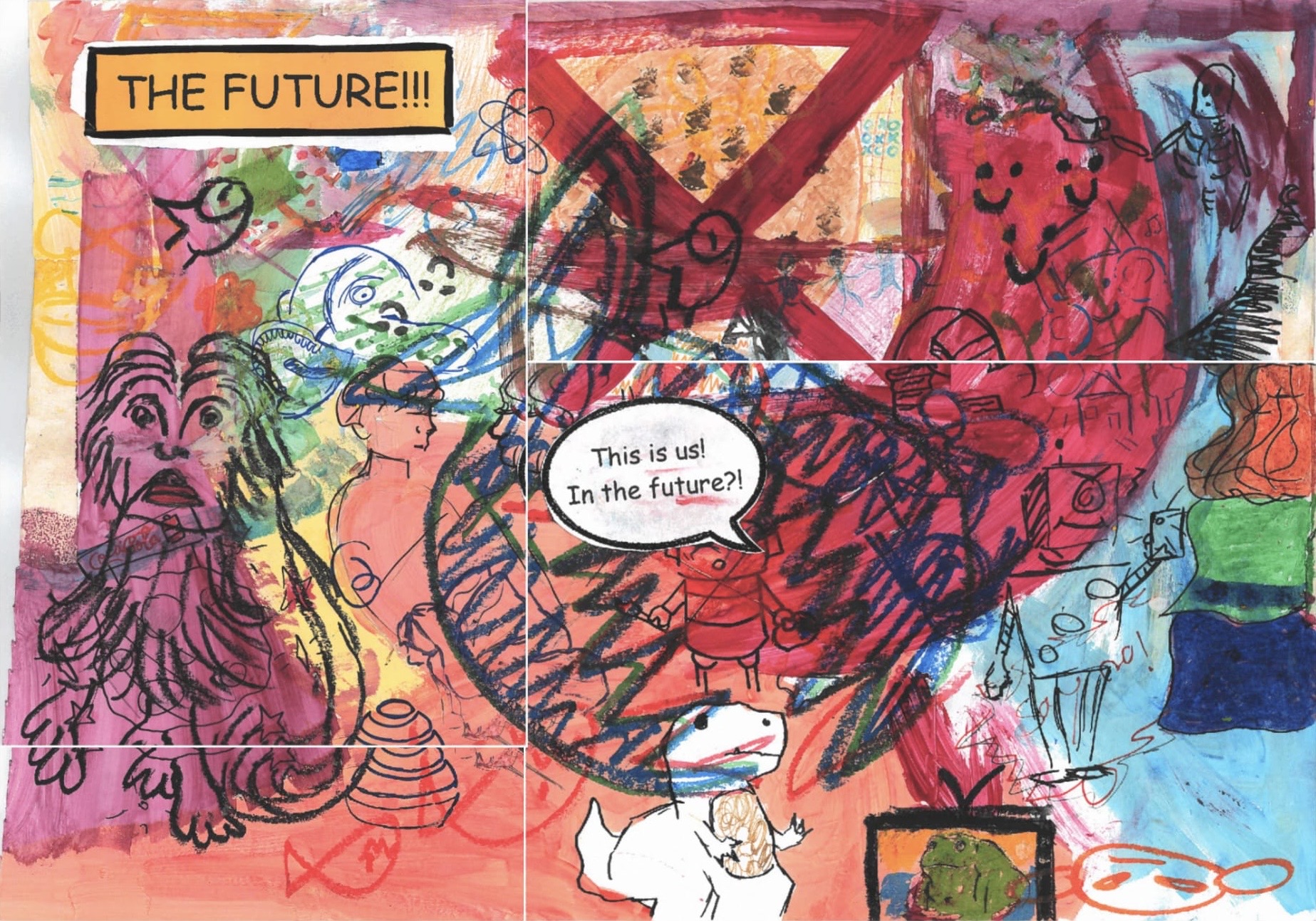

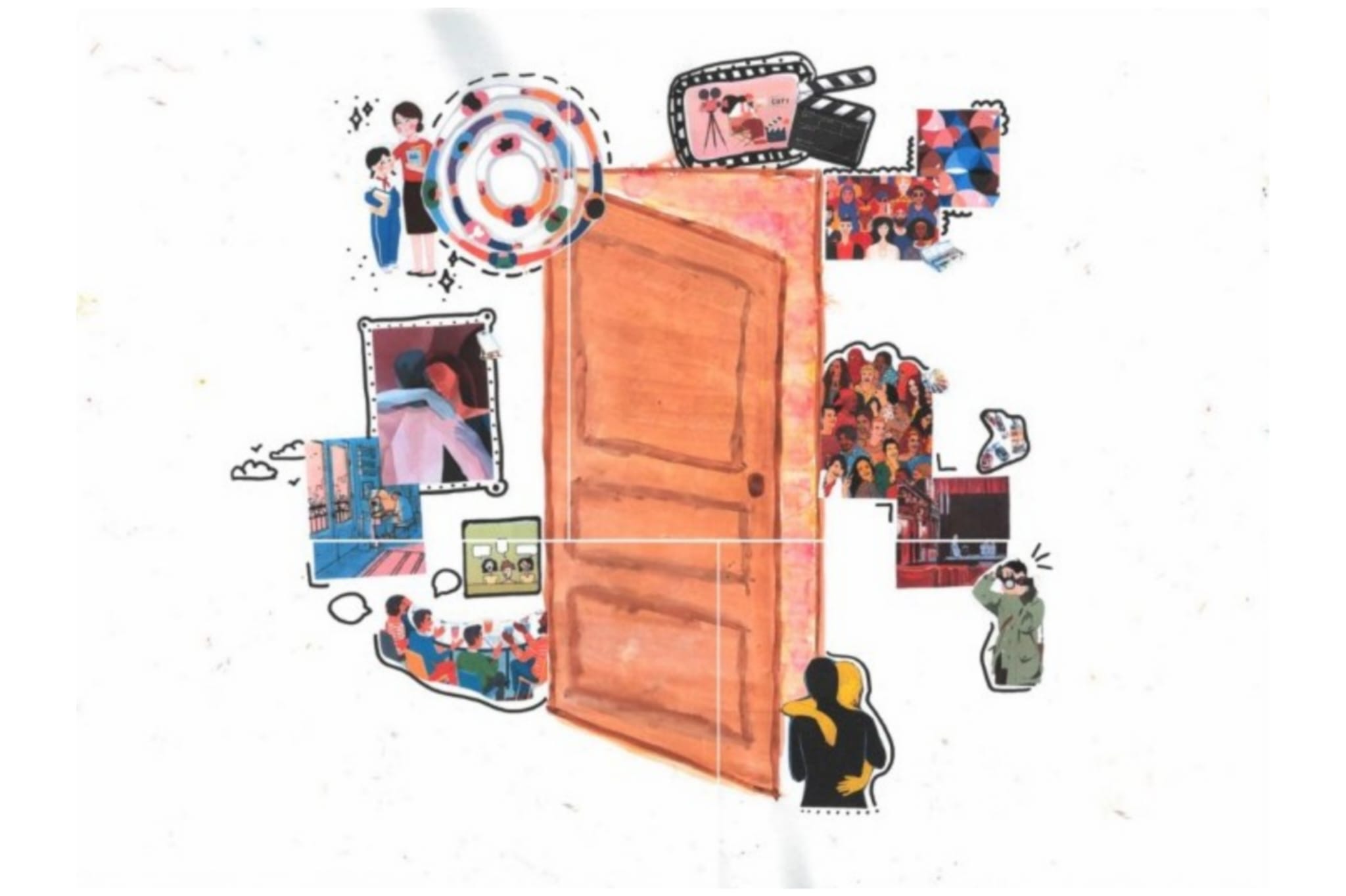

In class, these were transformed into three collaborative visual artworks, one devoted to each of the wishes, which are reprinted in this issue of BLIK (and this blog post). Especially now, at a moment of deep uncertainty about the world into which our students will graduate; especially now, when both the form and funding for arts, culture, and universities are under threat; especially now, as we see on full display the authoritarian impulses of the tech billionaires who own the platforms through which we communicate; now we need to both to understand our current system of media and culture and wish imaginatively about how things can be different. In that sense, these essays are a manifestation of my wish, both for the HHP (which has fortunately been saved from the most recent round of cuts) and for our wider academic endeavour, that we continue to learn from wishing out loud together: critically, creatively, and in community.

Leave a reply to Sleepdancing: an appreciation of James W. Fernandez | Alexander Badenoch Cancel reply