Somewhat against my wishes, I just received a new phone. I had defiantly had my old one repaired three times, but it was getting more and more temperamental, so rather than wait for it to die completely (as a single parent, I feel the need to be reachable at all times) I took the occasion of my contract expiring to get a new one. I had the last one for so many years, so I did not really know what to expect when I got a new one now. Hey, presto: you just put the new one next to the old one, and it just copies everything. It takes about 10 minutes.

Then, the old one asks me casually, almost chirpily, whether I want to erase it.

Though the phone makes no bones about it, it feels like that moment in so many science fiction movies when the android/computer that has been learning to be human is faced with mortality. Except this one is more like the cow that wants to be eaten from Douglas Adams’s Restaurant at the End of the Universe.

I checked the new phone to see that everything was there.

I checked again.

I checked one more time.

Everything obstinately persisted in its presence.

I waited a day.

Then hit ‘erase’.

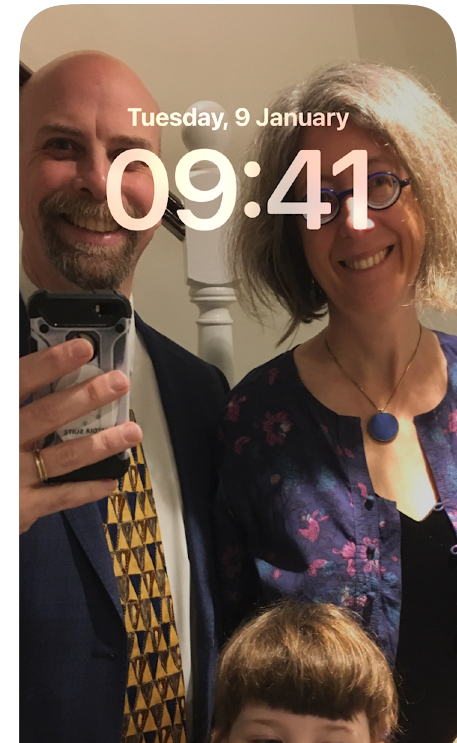

I can’t tell how many moments I witnessed through that phone. I can’t really remember when it took over from its predecessor, but on it were images from the birth of my daughter, the last visits with my mother, the last visits with my host mother, the death of my wife and everything after. Years of vital and mundane text messages. That now-little-seeming phone is even immortalized in the lock screen of my new phone, which was the lock screen of my old phone:

But that’s the thing: all of that was just passing through. For several years, I have taught a class where students read Wendy Hui Kyeong Chun’s seminal article “The Enduring Ephemeral, or the Future Is a Memory” where she discusses how with digitization, things aren’t so much preserved as perpetuated: called up and reassembled on demand. That is what media are: things that are passed through (though never simply, never neutrally). As a corollary, much as they are fetishized and always with us, the heavy material of our phones are also understood to be just passing through our lives, their obsolesence long-since planned. Retention and repair is actively discouraged: the promise is that the next one will be a useful palimpsest of the previous.

In Dutch, ‘stof’ can either mean dust (related to German Staub) or material (related to German Stoff, which comes from French). I used to joke – long before I came across this particular linguistic stretto – that things are like dust: they accumulate as soon as you stop moving. But it feels like I’m living with everything around me in a constantly ambiguous state between both senses of stof, and I am accordingly ambivalent toward things. It seems I spend about equal amounts of time explaining to my kid that things are just stuff and that their loss is not necessarily tragic, and reminding her to care for things and respect them. Like me, my kid is very iffy at the latter, but revisits the trauma of her mum’s loss in miniature whenever she loses or breaks things. With me, the emotional layering is a bit different: one minute I’m going through my untidy everyday life cluttered with familiar things, and then I blink and, viewed through grief, I am standing in the midst of ruins, where most things are a wrecked testament to what used to be my life.

It passes through, and I keep going.

Leave a comment